- February 20, 2025

Autonomous Driving: Bifurcated Markets (Part III)

This piece is part of a series. Click to read Part 1 and Part 2.

The future of the automobile has often been described as a “smartphone on wheels”—essentially a large mobile computer. But unlike smartphones, which benefitted from deep integration between the United States and China, advances in autonomous driving (AD) capabilities are being viewed through much more of a securitized and national lens.

Competitive tensions aside, thorny issues like data security, supply chain integrity, and regulatory regimes will prevent an interdependent US-China AD market from taking shape like it did in consumer electronics.

To be sure, Chinese capabilities today are at a point where it could largely go it alone on AD. It has a formidable EV industry, a manufacturing ecosystem, and plenty of artificial intelligence (AI) talent. As a result, AD will likely be both “Made in China” and “Made in America.” The competition will be about who deploys faster domestically, scales faster globally, and has better and safer products.

In the third and final installment of this series, we examine some of the barriers and challenges that will lead to a bifurcated AD ecosystem.

Data: Location Matters

AD systems need to feast on a constant stream of data to drive well and safely. The cameras and sensors all over that robot with wheels collect a mind bogglingly large—and potentially sensitive—amount of data daily.

For instance, if an autonomous vehicle (AV) drives into a highly secure military installation or government compound, it will have captured video of what it looks like—and it matters where that video data is ultimately downloaded. Plus, each AD company will have its own software to run its entire fleet of vehicles, making the company the single fail-safe for preventing glitches and hacks. Therefore, a trustworthy company is of utmost importance. Given the dearth of trust between the United States and China, neither side wants to hand over control of AVs to companies from the other.

This was evidenced by the previous Biden administration’s final rule on connected vehicles that explicitly restricts Chinese AD players from entering the US market. But the Chinese side has also been wary of operating in the US market for years: Chinese robotaxi firm Pony.ai pulled out of California in 2021 after its testing license was revoked. It was a decision made easier by the fact that its US operations contributed less than 1% of company revenue in 2023.

Tesla, of course, is really the single test case of whether the two largest AD markets are able to establish some connective threads. Despite the company’s efforts to comply with China’s data localization requirements, Tesla still has not received Chinese regulators’ approval for deploying its latest full self-driving (FSD) software.

One of the main hangups is where Tesla wants to train its FSD data: in supercomputing clusters in places like Austin or Memphis. But Chinese law requires the processing of multimodal driving data to be done in country. It’s a catch-22 for Tesla: train outside China with superior compute but inferior data resources or train inside China with inferior compute but superior data resources.

Tesla’s predicament reflects regulators’ genuine data security concerns. Getting that approval, however, would certainly boost the company’s valuation, since China is its most important market outside of the United States.

Deployment: Regulations and Infrastructure

Centralized vs. Federal Regulations

When it comes to AD deployment, China seems to be running ahead to its own beat, in part because Beijing has so far supported the industry’s development. In early 2020, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) and other agencies jointly issued supportive guidelines for AD, deeming it a strategic industry.

That high-level support has been followed by more concrete actions, as China’s Ministry of Transportation (MoT) and MIIT issued a national approval framework for robotaxis in December 2023. To get approval, a robotaxi service provider has to meet emergency response capabilities and insurance requirements, define use cases for AD providers, and use at least one human remote safety controller for every three robotaxis. Local governments, such as Beijing, Wuhan, and Guangzhou, have based their policies on the national framework.

Compliance costs for AD companies are much higher in the United States because of its federalized regulatory approval system. Launching robotaxi operations in the United States requires separate approval processes in states, each with their own distinct requirements for robotaxi operators. For example, Nevada requires AVs to have the ability to disengage the autonomous system, while New York only allows testing under supervision of the state police, and Texas mandates recording devices inside all AVs. More than a dozen US states have not even established approval processes or issued any relevant legislation.

Some of these regulatory barriers may be lowered under the new Trump administration. In his confirmation hearing, the Secretary of Transportation Sean Duffy decried the current patchwork of ad hoc state regulations and pledged to establish clearer rules at the national level. The AD industry also hopes the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration will lift the limit on robotaxi fleets to 2,500 vehicles—a threshold no operator has met yet (Waymo’s fleet of almost 1,000 vehicles is the closest).

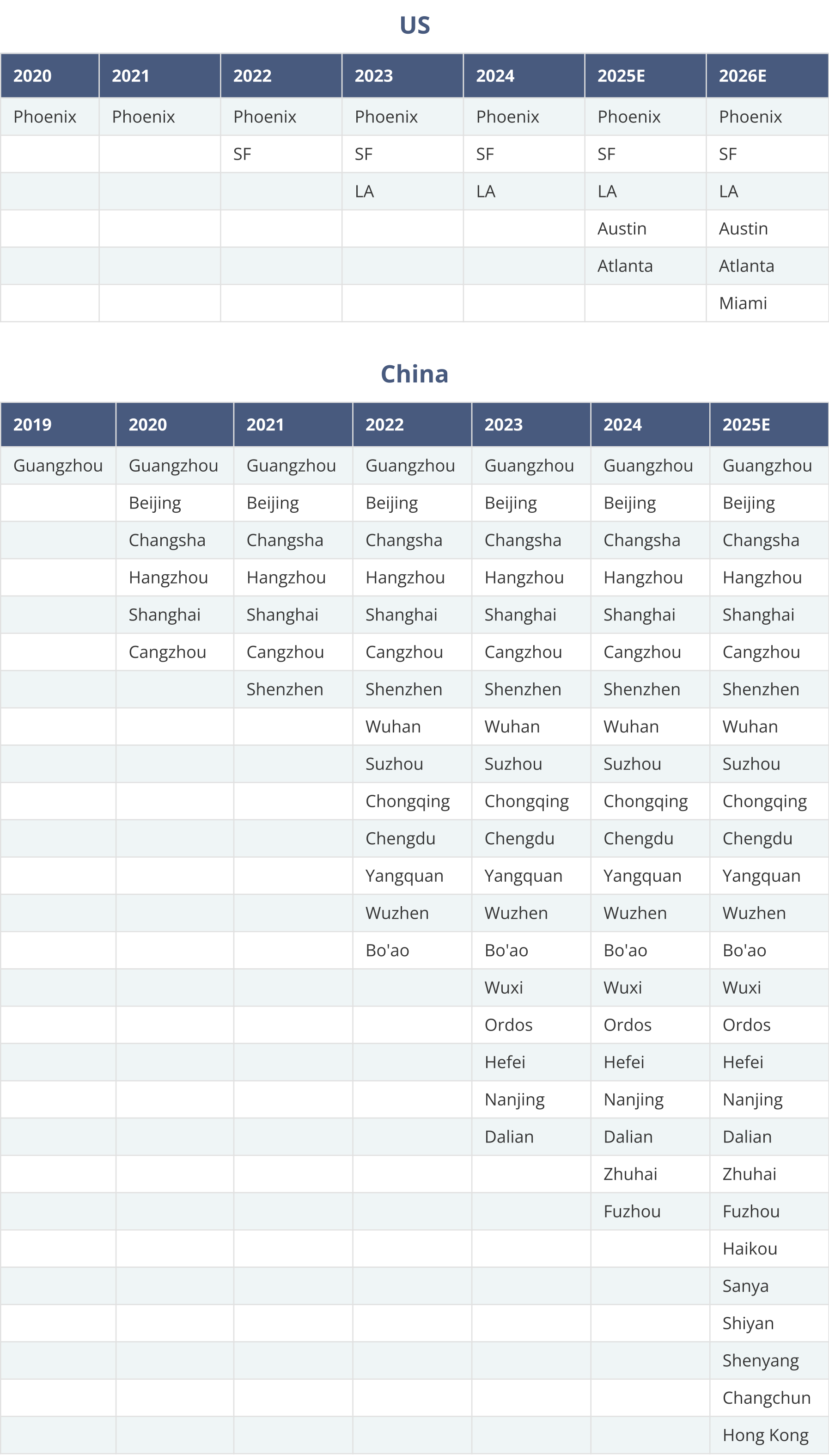

Despite this, Tesla has been eager to apply for AD licenses in China. That’s because with a national AD policy, once an operator is approved, it has access to a potential market of 1.4 billion passengers. In fact, domestic Chinese providers are already jumping into the fray. Since the AD starting gun was fired, around 20 Chinese cities now have active robotaxi services, far outpacing the expansion in the United States (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. China’s Scaling Advantage on Display in Robotaxis Source: Company announcements; local media reports.

Source: Company announcements; local media reports.

As of July, Baidu’s Apollo completed more than seven million robotaxi rides in China, surpassing Waymo’s five million. That gap is likely to widen as more domestic providers get the greenlight to operate.

No Chips? We’ll Build Highways!

China’s compute constraint will affect how well its companies can train the vision language models powering their AD systems. But what China lacks in compute, it hopes to offset by building connected infrastructure like smart highways. These are supposed to be dedicated, sensor-dense roads that allow communication across all AVs about potential hazards (like a pileup one kilometer down the road). These safety benefits can also spill over to traditional cars, which also drive on these smart highways.

Since MoT released guidelines for constructing smart highways in 2023, China has already designated 17 smart highway AD testing areas in 26 cities covering more than 32,000 km and featuring 8,700 roadside sensor units (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. China’s C-V2X Demonstration and Pilot Areas Cover 26 Cities

Communication between roadside sensors and AVs occurs via wireless radio waves, which rely on spectrum allocation. In the United States, some systems still rely on the older Dedicated Short-Range Communications (DSRC) technology, while China has broadly adopted the more advanced and modern Cellular Vehicle-to-Everything (C-V2X) system based on 5G.

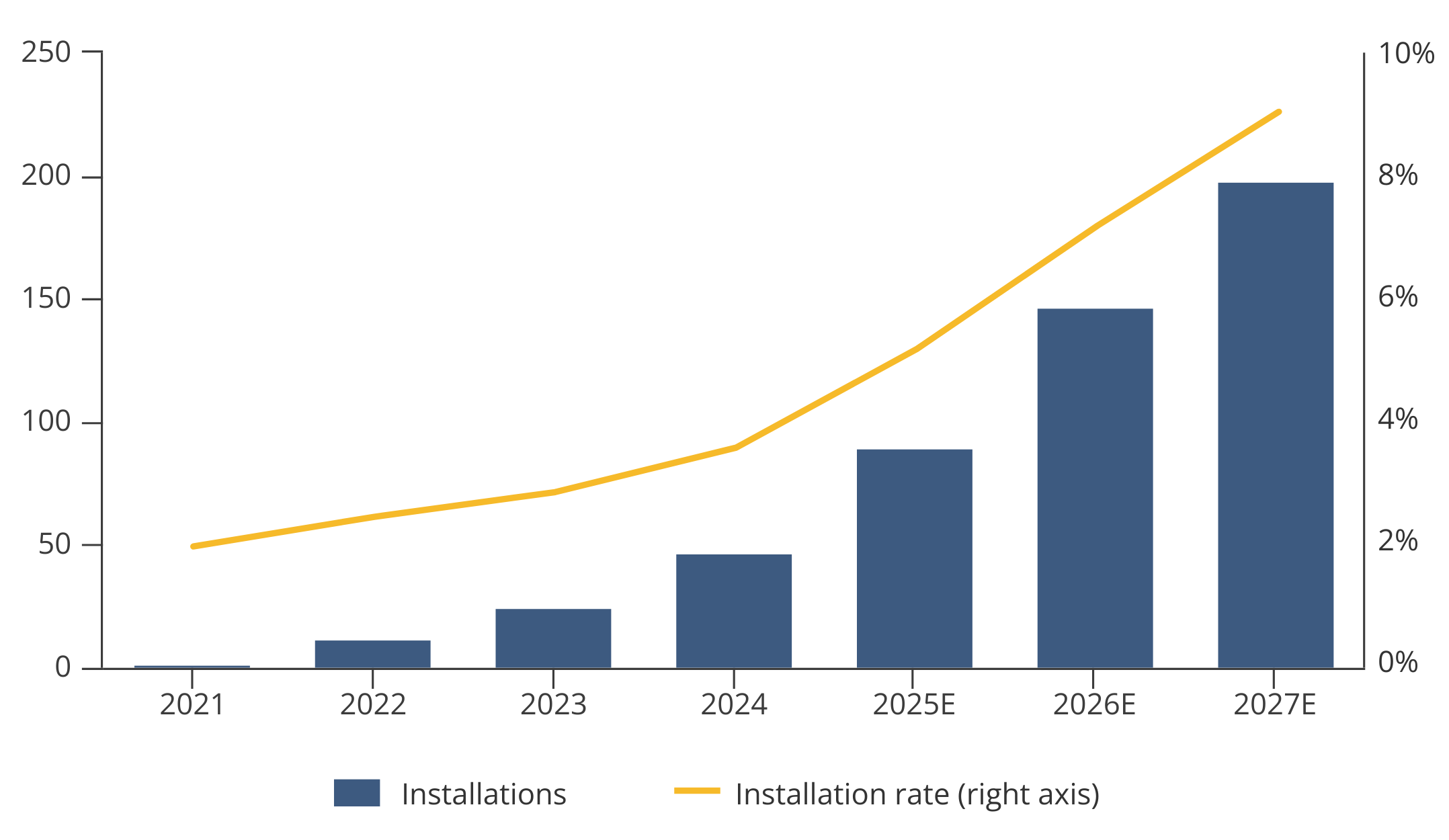

That system was prioritized from start of AD’s development in 2020 and represents one of the first tangible benefits from the country’s widespread 5G buildout (which has so far provided underwhelming practical solutions). Chinese automakers have been incorporating C-V2X compatibility into their vehicles already, and the proportion of compatible vehicles is estimated to rise sharply in the coming years (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Chinese C-2VX Penetration is Gaining Momentum

Source: ResearchInChina.

Widespread creation of connected highways creates another competitive advantage—but also potential security vulnerability—for Chinese robotaxi operators. In Guangdong province, a new agreement released last month leverages connected highways for intercity robotaxi operations between Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Zhuhai, and Macau.

While China seems to be backing the idea of making existing highways “smart” so that AVs perform better on them, US leader Waymo restricts its robotaxis from even driving on highways. Then again, building infrastructure has been one of China’s longstanding strengths, though the jury is still out on whether smart highways alone will materially matter in how AD develops.

Beyond regulations and infrastructure, each market will likely be relatively shielded from foreign competition, enabling two distinct and massive markets to incubate and mature separately. Notably, Tesla is looking to defy this expectation and become the only AD player active in both the US and Chinese markets.

Ultimately, AD’s bifurcated development in the United States and China means the spoils of commercialization will likely get split among a handful of major operators. Similar fault lines will emerge as competition to dominate the next generation of robotics intensifies.

AJ Cortese is a senior research associate at MacroPolo. You can find his work on industrial technology, semiconductors, the digital economy, and other topics here.

The author would like to thank Cedar Liu and Guanzheng Sun for excellent research assistance.

Stay Updated with MacroPolo

Get on our mailing list to keep up with our analysis and new products.

Subscribe