- September 3, 2019

Matters of Record: Relitigating Engagement with China

Debate over Washington’s decades-long policy of “engagement” with China has intensified in recent years. Within foreign policy circles, a growing and bipartisan chorus of voices is calling for the United States to abandon engagement because it failed to produce a liberal democracy in China that wholly accepted American global leadership.

While these facts are incontrovertible, such a singular litmus test for whether engagement succeeded or failed is incomplete and misleading. It is premised on a selective historical record and risks oversimplifying what was a complex and multi-faceted approach to China across successive US administrations.

History matters. That’s because a fuller appraisal of Washington’s rationale for engagement has direct implications for how Washington should deal with Beijing today. It also has the virtue of highlighting how the potted narrative of “failure”—which some have even used to justify a potential civilizational confrontation between the two countries—fails to capture the broader history of US-China engagement. In particular, a closer look at the administration of Bill Clinton is necessary, because many point to the “long decade” of the 1990s as when engagement took on the explicit aim of delivering political transformation in China.

This analysis is not a comprehensive account of the engagement strategy nor a holistic assessment of the beliefs held by policymakers. Rather, it analyzes a number of key policy documents from the Clinton administration that add nuance to today’s debates about what engagement was and was not. It briefly revisits the flourishing of engagement in the 1990s and outlines how the debate on China has shifted, before examining key speeches, national security strategies, and Clinton’s autobiography to illustrate that engagement was a balancing act with multiple objectives. Even if Beijing did not meet expectations of political change, some elements of Clinton’s strategy succeeded, and these are likely worth preserving in new approaches to China.

Apotheosis of Engagement

Contrary to some interpretations, the China policies of US administrations from Richard Nixon to Ronald Reagan were driven largely by the anti-Soviet geopolitics of the Cold War. But after European communism collapsed, the United States found itself the sole superpower in a world safer for democratic capitalism. A foundational principle of American foreign policy had suddenly dissipated, prompting a reconceptualization of Washington’s approach to China.

Numerous observers and critics think of engagement only as a policy intended to “enable” China’s rise that hinged entirely on the expectation that Beijing would become a liberal democracy that answered to US leadership.

That shift began during the presidency of George H.W. Bush (1989-1993), who first introduced the term “engagement” to describe his decision to maintain contact with Chinese leaders in the aftermath of the Tiananmen crackdown. But it was during the Clinton years (1993-2001) that an explicit “engagement policy” became closely associated with the idea that market openings would bring political change to China.

Today, numerous observers and critics think of engagement only in these terms—as a policy intended to “enable” China’s rise that hinged entirely on the expectation that Beijing would become a liberal democracy that answered to US leadership. That view is widespread, but also inaccurate and incomplete.

State of the Engagement Debate

While debates about engaging China are hardly new, their importance has risen amid Beijing’s more assertive foreign policy since 2013 and a dramatic shift in the prevailing consensus in Washington. In December 2017, the Trump administration released a National Security Strategy (NSS) that redefined Washington’s approach to China in a new era of “great power competition.” The NSS declared that previous administrations’ China policies had been mistaken because they had been “rooted in the belief that support for China’s rise and for its integration into the post-war international order would liberalize China.”

A manifestation of this new strategy took shape in the form of the US Trade Representative’s Section 301 report, released in March 2018, which laid the foundations of the US-China trade war. Since then, many voices, both within and outside the administration, have emerged to label engagement a failure, lament that Washington “got China wrong,” and call for a “reckoning” with how Beijing “defied American expectations.”

These debates reached a crescendo toward the end of 2018, when Vice President Mike Pence gave his now well-known speech at the Hudson Institute that October. He reinforced the notion that America had assumed “a free China was inevitable” and that China’s integration into the global economy would “bring China into a greater partnership with us and with the world.” That address prompted further critiques of engagement, singled out as the United States’ “greatest foreign policy failure” and responsible for “the resurrection of the Chinese monster.” Many seem to blame the stewards of engagement for being “naïve” or “blind” to Chinese realities.

What’s missing from this debate is a more expansive and hence more accurate assessment of what engagement was—an account that does not simply cherry-pick the words proved most wrong by time.

Amid bilateral disputes over trade and technology, and as some seriously advocate “full-spectrum competition” and “decoupling” with China, this debate continues and is unlikely to subside. Administration officials admit that it is nonetheless “trying to create an intellectually persuasive argument” to ensure bipartisan support of a more muscular approach toward China.

What’s missing from this debate is a more expansive and hence more accurate assessment of what engagement was—an account that does not simply cherry-pick the words proved most wrong by time. A study of public sources from the Clinton era indicates that engagement was not an “abject failure.” It had successes, even if it didn’t make Beijing a full-fledged partner.

Engagement Reexamined

In recent months, some scholars and former policymakers have revisited the Clinton era to push back on the “failure of engagement” narrative. Harvard’s Alastair Iain Johnston has shown that Clinton administration officials tended to make very qualified statements about the potential for engagement to achieve democratic change in China. Ryan Haas of the Brookings Institution, too, has argued that the idea of political liberalization was never the lodestar of China policy, although its rhetoric was sometimes used to shore up domestic support.

Yet, with the passage of time, many of Clinton’s speeches, administration strategies, and even his personal writing have faded from view and still receive scant attention in today’s China debates. These primary sources paint a far more nuanced picture of engagement.

Rhetoric: What Did Clinton Actually Say on China?

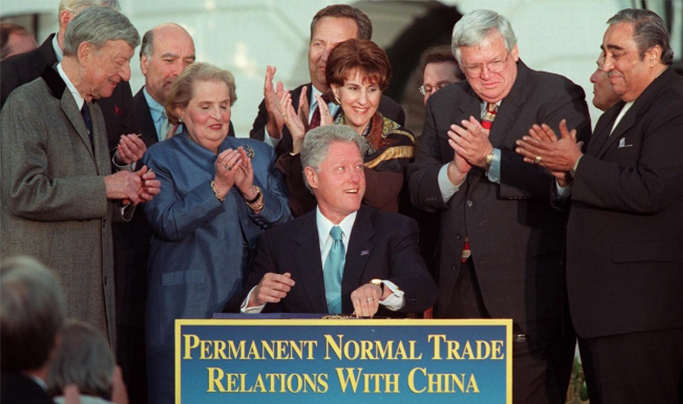

Many current depictions of Clinton’s China policy, and even of US engagement more broadly, draw heavily on a single speech that he delivered at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced and International Studies (SAIS) on March 8, 2000. At the time, Clinton was urging Congress to grant Permanent Normal Trade Relations (PNTR) to Beijing and thereby allow the United States to benefit from China’s accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO).

That speech included soaring Clintonian rhetoric about how WTO accession meant China was “agreeing to import one of democracy’s most cherished values: economic freedom” and how Beijing “will find that the genie of freedom will not go back into the bottle” as “liberty is the most contagious force in the world.”

Yet that SAIS speech was the fourth in a quartet of major Clinton speeches on China policy, which collectively present a more pragmatic version of engagement. It seems plausible that the president dialed up emotive arguments in this fourth speech so that Beijing’s WTO membership would resonate more with a skeptical Congress. Indeed, many on Capitol Hill at the time were beginning to question free trade and globalization.

Take Clinton’s first major speech on US-China relations from October 24, 1997. Titled “China and the National Interest,” it was given to Voice of America (VOA) shortly before President Jiang Zemin arrived for the first state visit by a Chinese leader since July 1985.

In this speech, Clinton said China was “at a crossroads” as an emerging power and that the US national interest lay in a China that was “stable, open, and non-aggressive” rather than one that “turned inward and confrontational.” The president argued for a “pragmatic policy of engagement” that involved “expanding our areas of cooperation with China while confronting our differences openly and respectfully,” in order to “advance fundamental American interests and values.”

He expounded on six areas of “profound interest” that undergirded engagement: 1) promoting a peaceful, prosperous, and stable world; 2) peace and stability in Asia; 3) controlling weapons of mass destruction; 4) combatting drug-trafficking and organized crime; 5) keeping trade and investment as free, fair, and open as possible; and 6) fighting climate change.

The president argued for a “pragmatic policy of engagement” that involved “expanding our areas of cooperation with China while confronting our differences openly and respectfully,” in order to “advance fundamental American interests and values.”

Clinton believed that progress in these areas would “draw China into the institutions and arrangements that are setting the ground rules for the 21st century” and was the United States’ “best hope” for advancing its interests and values. Though he said that it would be increasingly difficult to maintain a closed system amid growing interdependence, Clinton also was clear-eyed that “China will choose its own destiny.” Practical interests in cooperation meant that engagement made sense even if the two countries disagreed on political values.

Clinton’s second China speech on “U.S.-China Relations in the 21st Century” was given to the National Geographic Society (NGS) on June 11, 1998, two weeks before the first China visit by a sitting US president since February 1989. That speech restated the interest-based framework for cooperation from Clinton’s VOA speech. But it also framed the US-China bilateral relationship as one of immense consequence that “will in large measure help to determine whether the new century is one of security, peace, and prosperity for the American people.”

It was in this NGS speech that Clinton stated plainly that “I do not believe increased commercial dealings alone will inevitably lead to greater openness and freedom,” but instead maintained that America could “most effectively serve the cause of democracy and human rights within China” through engaging with its leaders and society. He also stressed that “principled and pragmatic” engagement with China was the choice of key regional allies such as Japan, South Korea, Australia, Thailand, and the Philippines, and so unilaterally spurning China would only isolate the United States and make the world less safe.

On the eve of Premier Zhu Rongji’s official visit in April 1999, Clinton, in a third speech on China, reiterated how practical interests underpinned US-China engagement. Speaking at the US Institute of Peace (USIP), Clinton also acknowledged that China may “choose” to pour “much more of its wealth into military might and into traditional great power geopolitics.” Yet this outcome was “far from inevitable,” so Washington “should not make it more likely that China will choose this path by acting as if that decision has already been made.”

While Clinton was optimistic about political liberalization in China, advancing American interests by deepening economic relations and securing Beijing’s cooperation on important global issues was of equal if not greater concern.

Clinton was also resoundingly clear that no one should assume that “engagement alone can give rise to political reform in China” but commercial ties did help Chinese people become freer in choosing “where they work, and where they live, and where they go.” He concluded that “while we cannot know where China is heading for sure, the forces pulling China toward integration and openness are more powerful today than ever before.”

Analyzing Clinton’s major speeches on China suggests that, while Clinton was optimistic about political liberalization in China, advancing American interests by deepening economic relations and securing Beijing’s cooperation on important global issues was of equal if not greater concern. Clinton may have mostly omitted such practical arguments for interest-based cooperation from his SAIS speech on China’s WTO accession, but the full record of his speeches on China indicates that engagement was not predicated on Chinese democratization.

Actions: What Were Clinton’s Actual Policies and Strategy on China?

Beyond Clinton’s speeches, his administration’s policies on China were articulated in his various NSSs, the document in which the White House communicates the broad strategic priorities and basic parameters of US foreign policy. Not every president delivers an annual NSS, but Clinton published one each year from 1994 to 2000. These documents offer a general overview of Clinton’s foreign policy thinking, and consistently suggest that his administration never saw political change in Beijing as a major foreign policy priority.

Clinton’s seven NSSs all offer slight variations on the same three overarching themes for American foreign policy: “Enhancing Security at Home and Abroad,” “Promoting Prosperity,” and “Promoting Democracy.” These “mutually supportive” goals together formed a virtuous circle: secure and stable countries were more likely to support trade and maintain democracy, open economies were more likely to feel secure and pursue freedom, and democratic polities were more likely to cooperate with Washington on security threats and market development. It was a strategy of “engagement and enlargement.”

These NSSs stated the administration’s policy toward China as one of “broader engagement” or “comprehensive engagement” that encompassed both “economic and strategic interests.” This policy’s main goals were generally to prevent China from emerging as “a security threat,” to promote “China’s participation in regional security mechanisms,” and to encourage “a more open, market economy that accepts international trade practices.”

Take the 1996 NSS as an example. It said that Washington sought a “strategic relationship” with Beijing that advanced “core national security interests while keeping in mind longer-term goals.” That goal would be pursued by seeking to “integrate China into the international community as a responsible member” and “foster bilateral cooperation in areas of common interest.” Clinton then wrote, in his preface to the 1997 NSS, that engagement was essential to “prospects for peace and prosperity in Asia” and was “the best way to work on common challenges such as ending nuclear testing—and to deal frankly with fundamental differences such as human rights.”

Press conference with Zhu Rongji and Bill Clinton, 1999

Press conference with Zhu Rongji and Bill Clinton, 1999

Source.

From these abstract interests emerged a consistent and concrete set of actionable goals that defined US strategy on China under the engagement policy. These included increasing bilateral dialogues, preventing WMD nonproliferation in East and South Asia, preventing the nuclearization of the Korean Peninsula, cooperating on disease and environmental issues, better market access and intellectual property rules, fighting organized crime, ensuring stability in the Taiwan Strait, and WTO accession on “commercial terms,” among others.

Although the space devoted to China in the NSS increased over time, the strategy still made no mention of Chinese democratization, except to say that the United States sought “progress” on human rights in China, including religious persecution, human trafficking, and the rule of law. Democracy promotion, one of the three pillars of Clinton’s NSS, focused mainly on Russia, Central and Eastern Europe, and smaller countries in Africa and Asia.

Perhaps Clinton’s final NSS in 2000 best captured his administration’s overall foreign policy of engagement. It cautioned that while “some may be tempted to believe that open markets and societies will inevitably spread in an era of expanding global trade and communications,” that assumption ignores “the defining features of our age: the rise of interdependence.” Because US progress depends on the progress of others, “America can advance its interests and ideals only by leading efforts to meet common challenges.”

Therefore, progress necessitated cooperation with China, where engagement was focused on dissuading Beijing from “regressing” into confrontation while encouraging “important political and economic reforms.” A common theme that appeared again in this last NSS was to incentivize China’s participation in the global system as a responsible member of the world community. The document even admitted that the outcome of engaging China was “not altogether certain” but was worthwhile as the process “has had a positive impact on both regional and global stability.”

It’s worth noting that, at this point, the Clinton administration had already secured Congressional support for China’s WTO accession, creating as good an opportunity as any for Clinton to include language about how trade and economic integration would supposedly bring political change to China. Yet the NSS simply stated that WTO accession would “create jobs and opportunities for Americans through the opening of Chinese markets, promote economic reform in China, and enhance the understanding of the Chinese people of the rule of law in the development of their domestic civil society in compliance with international obligations.”

Engagement with China was not primarily aimed at changing China, but rather focused on benefitting America.

This framing is neither a triumphant celebration of inevitable democratization nor a credulous declaration of China subsuming itself to American leadership. Instead, it comports with the dominant argument used by PNTR advocates to sway legislators. That is, engagement with China was not primarily aimed at changing China, but rather focused on benefitting America.

Reflection: How Did Clinton Write About China in His Autobiography?

But what did Clinton actually think about China, beyond his words in official speeches and policy documents? George H.W. Bush, in a 1998 book, said he thought that Chinese democratization was inevitable. Ruminating on his decision to engage with Beijing after Tiananmen, Bush wrote, “I believed that the commercial contacts between our countries had helped lead to the quest for more freedom. If people have commercial incentives, whether it’s in China or in other totalitarian systems, the move to democracy becomes inexorable.”

Clinton too appeared to have been optimistic, but actually somewhat less Panglossian than Bush. In his 2004 autobiography My Life, well before any reversals on China in Washington that could have prompted him to reconsider this legacy, Clinton commented on several major events in bilateral relations that shed light on his attitude toward China while president.

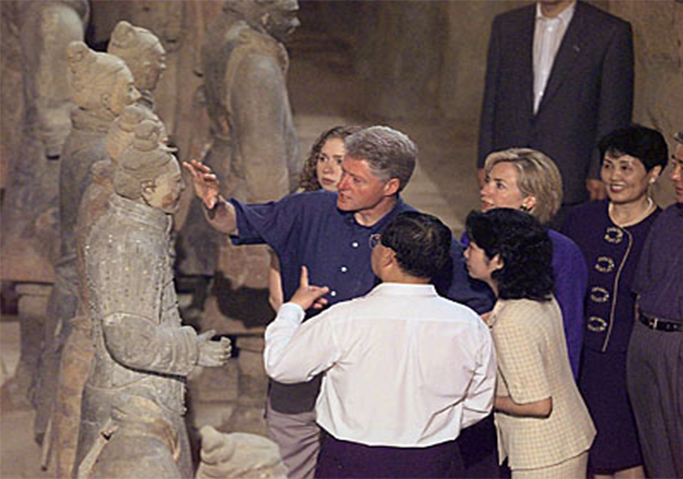

The Clinton family visit the terracotta warriors in Xi’an, 1998

The Clinton family visit the terracotta warriors in Xi’an, 1998

Source.

He seemed too hopeful when, after meeting with President Jiang in Washington in October 1997, he thought “that China would be forced by the imperatives of modern society to become more open, and that in the new century it was more likely that our nations would be partners than adversaries.” But he also thought that Chinese leaders were “managing all the change they could handle with their economic modernization program.” These were hardly the thoughts of a starry-eyed president who believed political change was imminent in China.

Clinton thought it was inevitable that the United States had to work with China to manage international issues. Washington had no hope, in Clinton’s view, of increasing regional security or addressing global threats or advancing human rights in Asia unless Beijing had an incentive to participate:

With a quarter of the world’s population and a rapidly growing economy, China was bound to have a profound economic and political impact on America and the world…The United States had a big stake in bringing China into the global community. Greater trade and involvement would bring more prosperity to Chinese citizens; more contacts with the outside world; more cooperation on problems like North Korea; greater adherence to the rules of international law; and, we hoped, the advance of personal freedom and human rights.

Engagement Reconsidered

Whether Clinton and other policymakers completely stood by their words is impossible to know. Perhaps declassified records will reveal more in the future, but at this point the public sources reveal both a genuine expectation of some liberalization in China’s internal governance and external behavior, and a litany of interest-based strategic objectives.

Of course, China did not turn into a democracy, and if engagement is pegged to that singular expectation, then it failed. But judged by the Clinton administration’s actual goals and priorities on China, the policy was more successful. On many global issues, Washington was able to persuade China to cooperate, compromise, or otherwise increase its support for American preferences. And the two countries established regular working-level exchanges and bilateral accords across a range of areas, from law enforcement and disease pandemics to environmental issues and military maritime safety.

Beijing also supported Clinton’s campaign to freeze the North Korean nuclear program and helped lead global responses to cool an India-Pakistan nuclear arms race. China signed the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty, enacted the Chemical Weapons Convention, committed to the principles of the Missile Technology Control Regime, and tightened export controls on military technology. Beijing also contributed more to multilateral institutions and fora like APEC, ASEAN, the World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund.

Even support for China’s WTO accession—arguably the most controversial aspect of Clinton’s engagement policy today—was a net benefit. It did not bring democracy but it did bring many of the economic benefits that Clinton had focused on in the first half of his SAIS speech. The trade specialist Scott Lincicome has already demolished the many arguments that granting PNTR to China was a mistake. Even David Autor, one of the authors of the “China Shock” paper that influenced trade debates during the 2016 election cycle, notes that China’s global integration both raised US GDP and was “enormously positive for world welfare.” The core problem was that the costs of trade were highly concentrated in specific sectors and domestic policy did not adjust sufficiently to redistribute the gains of trade from winners to losers.

Bill Clinton signs the act that implemented PNTR for China, 2000.

Bill Clinton signs the act that implemented PNTR for China, 2000.

Source.

Engagement continued to be partially successful after Clinton. Earlier this year, economist David Dollar identified eight international issues on which the United States had “intensively” engaged China, finding that Beijing had aligned with Washington’s preferences on climate change, nuclear nonproliferation, and global trade and currency imbalances in previous administrations. Dollar also found that engagement had helped ensure China acted “as to be expected” on issues of development assistance and intellectual property rights protection, though the policy recorded “disappointing failures” in securing market access for US firms, ending militarization of the South China Sea, and promoting democracy and human rights.

Where engagement succeeded it was generally due to a few notable factors: strong and consistent diplomacy by the United States, added pressure from America’s international partners, and incentives created by multilateral institutions. A combination of these factors could affect how China perceived and pursued its interests. Policymakers always knew that China’s direction was ultimately set in Beijing—as Clinton recognized—and engagement was simply the best option to positively influence a process that America could not dictate.

Ultimately, as others have pointed out, a major flaw in critics’ casual dismissal of engagement in the 1990s is their failure to answer a simple question: What was the alternative? If Clinton had tried to block China’s participation in the international order, the country could have become a turbocharged Iran, but 15 times larger and already nuclear-armed. It would have been isolated, insecure, and potentially intent on disrupting peace and prosperity in the US-led regional order.

The “failure of engagement” narrative often rests on the assumption that China’s expected liberalization was the decisive reason behind Washington’s engagement with Beijing. Yet the public historical record casts doubt on this argument. Clinton did once say an increase in the “sphere of liberty” was “inevitable” in China, but he also talked a lot of common sense:

We must build on opportunities for cooperation with China where we agree, even as we strongly defend our interests and values where we disagree. That is the purpose of engagement. Not to insulate our relationship from the consequences of Chinese actions, but to use our relationship to influence China’s actions in a way that advances our values and our interests.

One suspects that many critics today would actually agree with this statement. Yet the partial success of Clinton’s policy does not mean that engagement should not be reassessed. Every major policy requires adjustments as the world changes and challenges evolve. But simply declaring engagement a failure does a disservice to the achievements of previous administrations and ignores the potential calamities averted by that policy. When it comes to issues that do not threaten China’s political bottom line, bilateral diplomacy, international coalitions, and multilateral institutions are elements of the engagement policy that have proven and remain effective in pursuing certain American goals with Beijing.

Beijing was always going to make its own decisions and demand more of a say in global affairs—there should have been nothing surprising about this development—but positive-sum cooperation and global order often serve Chinese interests and shape Chinese choices. So, a United States that does not work out how to refine and improve its engagement with today’s China has far less hope of influencing Beijing’s actions, leveraging allies and partners, or fashioning effective responses to global challenges.

Stay Updated with MacroPolo

Get on our mailing list to keep up with our analysis and new products.

Subscribe