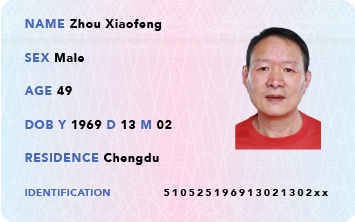

This blue-collar migrant spills his thoughts in his diary on the eve of his 50th birthday, reflecting on being a migrant for decades in Chengdu and longing for his family.

February 8, 2017

Next week I’ll turn 50 and I’m anxious about it. Maybe because of it, just last night I had another one of those recurring dreams where I was chasing my ambition of becoming a restaurant owner in Shanghai. I would bring the most authentic and delicious Sichuan cuisine to the wealthy Shanghainese, leaving my patrons’ mouths on fire for hours but wholly satisfied. I would charge those urban elites a premium and would build my restaurant, “Little Red Chilies” (小辣椒), into a franchise. People might even look at me and see a “restauranteur,” wouldn’t that be grand!

I would settle in Shanghai with my family and never look back, never worry about money, never be apart from my daughter again…

It all seemed to work itself out in the dream; I guess that’s what dreams are for. But then I was jolted awake by the loud speaker blaring a few blocks away. Ah, the middle school kids are doing their morning exercises again, and I was my insignificant self again.

Twenty years flashed before me, and I’m still just that chef in that quaint neighborhood restaurant on the edge of Chengdu. Few people see me all day, except for the line cooks in the back with me. Whatever ideas I had for reimagining Sichuan cuisine have long faded. Imagination is wasted these days, I try to keep it simple. What I look forward to each day now is using my trusty old wok that I’ve had for 10 years. It has soaked up so much flavor and it cooks well. I very much enjoy my wok!

It sounds trivial, but it’s these small things that define my life now. I never made it in Shanghai…now I cook for someone else rather than for myself. At least I get to run my modest kitchen. Maybe this is my calling, to work for a generous boss and feed customers cheaply, most of whom are migrants like me. At least my food will give them the energy to put in another 10 or 11 hours for the next day’s hustle.

Compared to them, I have it good—for an old geezer getting long in the tooth anyway. A stable job and steady income. It isn’t much, but it’s enough to get by on my own. What can I really expect for someone in my social situation, with barely anything to my name and without family. It has been ten years since my wife unexpectedly died, she was too young and I was lost. Well…I don’t want to say much more on this.

My daughter, I thought maybe she would stay to take care of me, but after her mother passed, I think my state of mind drove her away. Or maybe it was her ambition—I could tell early on that the migrant life wasn’t for her and she didn’t want to become just like her dumb, uneducated father. What could I do? She takes after me and dreams big.

When I get lonely, which is more frequent now, I like chatting up these young migrants that come through the restaurant. They remind me of my daughter, energetic and optimistic, but perhaps too idealistic. This new generation of migrants isn’t built like us in the old days—they can’t eat as much bitterness and they have unrealistic expectations. I don’t know where they’re getting all these ideas from, that they can start their own businesses and get rich and live like the wealthy city folks. They don’t stay in a job for long, constantly moving from gig to gig. I ask them if they want to get married and settle down, many of them tell me they don’t have time to think about that kind of stuff.

Yes, they really do sound just like my daughter, very little appreciation for stability. I can’t stop thinking about her these days and want to visit her. I know she won’t want me to—I think she’s embarrassed by her country bumpkin dad mingling with her sophisticated friends and colleagues. She doesn’t communicate with me often, and I only catch snippets of her life from sporadic WeChat postings. I know running her own company must be very tough, but I wish we would talk more. She did write me an actual letter about three months ago. And I tell ya, I was so giddy when I received it that I read it ten times and put it next to my bed.

So these days, I have few outlets other than jotting down my thoughts. No one wants to hear them, but it reduces my anxiety when I just keep on scribbling for myself. I don’t think my situation is unique, but the life of a humble migrant is all that I’ve known and it’s worth reflecting on.

Living on the Migrant Side

Except for my brief and failed stint in Shanghai, where I shared a cramped studio with other migrant acquaintances, my family and I have rented a one-bedroom apartment in Chengdu for at least 15 years. The pace of life here is just about right, not too hectic like in Shanghai. Nobody looks at you in Shanghai, they just move pass you quickly and often with an expression of annoyance. Here, I can stroll and occasionally even smile at strangers.

When we arrived in the provincial capital in 2001 from our small mountain town in Huidong County, we bummed around for a while before finding a decent rental right on the city’s periphery, where a migrant community had been forming for a few years.

Even though I now live alone, I’ve kept the same place and pay about 850 yuan a month, just about 15% of my monthly income—and if I worked for a local danwei, I could’ve gotten more housing subsidies and perhaps even free company housing. But I prefer renting privately from a land lord who has been kind to me, only raising the rent 50 yuan over the last five years—I think he felt sorry for me after the situation with my wife and he knows I never skip rent. Many migrant families I know are in the same boat, resigned to renting for the rest of their lives. The lucky few have squirreled away enough savings to buy a place, but what do I need to own for at this point? I’ve lived in Chengdu this long without a proper hukou, what’s another 20 years?

My place is unremarkable but it holds memories. I’ve kept the day bed that my daughter slept on exactly the way it was, even the blankets and pillows I haven’t touched. She might want to sleep there again when she visits me, someday. And unless she asks me to move closer to her, this is where I plan to live out the rest of my life.

And why not? My neighbors are nice enough, even though I hardly interact with them these days. Most of them, like me, want to stay in Chengdu long term. It sure beats toiling away back in their villages, even if some of them still own some plots of land. I’ve been there, it’s grueling and not for old men like me. Cooking the food is much more enjoyable than planting the food!

Some of the younger couples that recently moved into the community often check on me, and they invite me for dinner during Spring Festival. They are constantly encouraging me to join community associations or elderly group activities. But I’d rather be left alone these days, I don’t want to bother people with my thoughts—they are my problems, not theirs.

Cooking All Day

Besides, I hardly have any time to enjoy myself because I’m still putting in seven days a week at the restaurant. Other than Spring Festival, I get a few days vacation here and there, but I can’t slow down yet. And it’s still my kitchen—the line cooks aren’t ready to take over, they need more experience. My monthly salary of 6,000 yuan isn’t bad, but I need to save more for that day when I must slow down. When it does, I’m going to need all the savings I can get. Like most migrants, I don’t have a pension or health insurance, I’m on my own when I retire.

Consuming myself in work also helps to divert my thoughts from my life and my daughter. She is so accomplished, graduating from college and becoming her own boss in the big city!

I’m very proud of her, though if I’m being honest, I sometimes secretly wish to be in her shoes. Maybe if I had the same opportunities she does now when I was younger, I could’ve made more out of myself. Book learning was never my strength, and I dropped out in high school to help on the family farm. But I was always curious about the world, and one thing I excelled at was selling our vegetables to city folks in Chengdu. I would always out-sell the vegetable and fruit stalls next to me. I’m not bragging when I say I had a knack for business.

Ah but what am I talking about…that was a lifetime ago. I wasn’t smart enough to start my restaurant, or perhaps it was because I gave up too easily. Some of my friends at the time said it was because I was naïve, that I thought the Shanghainese would treat me equally. They may have looked at me and saw all the features of a migrant, but I think I had the drive. I didn’t prove myself enough to them.

Here I go again, dwelling on what could’ve been. My business now is taking care of myself and my customers.

“Mahjonging Alone”

I figure I have another 10-15 years of “healthy” life left, so I’ve got to maximize that. I try exercising in the park whenever I can, and even walk to work on nice days. On weekends, on the occasions when I’m not working, I have little energy to go out. But that’s okay because I’m obsessed with American classic movies, and my DVD collection is very good. I’ve watched “Gone with the Wind” 20 times!

My neighbors often call on me on Sundays to play mahjong with them. I have to say that I don’t particularly enjoy the game, but what I love are the tiles. I’ve now collected more than a dozen mahjong tile sets and in my spare time, use them to set up dominoes around my apartment. I just love the noise they make when I push them over—and every time the neighbors’ kids hear the noise, they rush downstairs to see. It delights them. So I’ve promised them that they can help me build the largest possible domino set that would fit in my place. I’m already up to 20 mahjong sets.

When I retire, a normal person my age would probably spend most of their time taking care of and doting on their grandchildren. Whether that’s in my future too I cannot say. Some of the young couples suggest I get a dog—they even suggested that I should try one of those new online dating sites to find another wife. That’s ludicrous, I’d rather get a dog.

I don’t know if I’m made for retirement, too much time on my hands isn’t the best idea. Perhaps I’ll keep on working and moving, I can always drive for Didi or just be my daughter’s personal chef. She’s going to need one because she works too much…

Acceptance and Longing

It’s been three hours and my hand is getting sore. I don’t know how many pages I’ve filled but it certainly feels good to empty my thoughts. I didn’t mean to lament about my life or get overly sentimental. Just the opposite—I want to move toward contentment. Many migrants in my generation tell me they’ve “resigned” to their lot. Well, I think acceptance is better than resignation.

My circumstances dictated my opportunities and what I became—some of it was in my control, most of it not. At my age, that’s probably the one thing that truly gnaws at me: powerlessness. Powerlessness to shape my own destiny and to improve my lot. Acceptance is simply the logical mental state to deal with powerlessness.

But the one thing that I have not yet accepted is the gulf between my daughter and me. That is not something out of my control, and if I could just see her in person, I can convince her why we need each other and why I’m there for her.

Yes, this is my new calling.

In Their Own Words

We interviewed real migrants in similar cohorts to magnify their lives. Listen to each about their experiences, worries, and hopes.

To listen to other migrants’ stories visit the profiles of Yan Zi, a white-collar migrant, and Luo Xinnan, a teenage Dreamer.

Other migrant stories

Hukou Difficulty Index