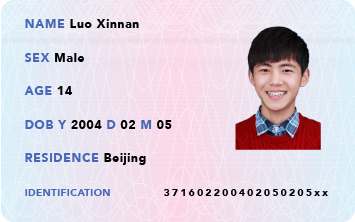

This teenage Dreamer, intensely stressed that he is being forced to return to laojia (hometown) in Shandong, writes a letter to his grandmother. He was raised by migrant parents in Beijing and knows no other home.

Dear Grandma,

I miss your dumplings at Spring Festival. Mom and dad say they make them just the way you do, but they never taste the same. I think maybe it’s because the water back in Shandong is cleaner than in Beijing.

When will you and grandpa visit me again? Now that it’s May, Beijing is finally warm and the streets are getting crowded. I want to show you all the parks in the summer, they are quite lively and many grandmas and grandpas hang out there. Sometimes you even get to see foreigners! I bet you don’t see foreigners in Binzhou.

I bug my parents to take me, but they work so much that they hardly have the energy or time. Lately, they’ve been working even more than usual, the stress worn on their faces becoming more severe. When I ask what’s worrying them, they dismissively wave their hands and always give the same response, “everything is fine, just focus on your school work and excel on your exams.” But I have a feeling it’s me, and my future, that’s bothering them.

This is why I’m writing you, because I’m very worried myself and I don’t have many people to talk to about this. Besides, of all people, I know you will understand my feelings.

I’m afraid mom and dad will send me back to Binzhou for high school. They think I can’t get into a decent high school in Beijing without proper hukou; they’d rather have me take the gaokao (university entrance exam) in Shandong and then attend a local provincial university. I think they have been working so much lately to send you more money in the hopes of taking care of me when I return.

They think I’m a naïve teenager who doesn’t understand the reality. But I am almost in high school! Our life hasn’t been easy, but we haven’t complained, as long as we can struggle through it together. I’ve even started to help out my dad with making deliveries on the weekends—one of his new part-time jobs—just so he can have a little down time.

I can see how hard my parents have to work just so I can get as decent an education as possible. They’ve put most of their savings into my education, which has allowed me to transfer from a migrant school to one of the few Beijing middle schools that have started taking migrants. I know they have all their hope riding on me as the first to graduate college.

Then why do they want to separate us? I told you over new year’s how well I am doing in school and how I have a close circle of friends who support me—some of them are even locals. But what I didn’t tell you was that for the past few months, my parents enrolled me in a private education center in Beijing, called Future Capital, one of the first of its kind to help migrant students like me to carve out a better future.

The people at the center were so kind, they offered to help my parents with paying some of the fees. After the first day, I never wanted to leave that center, the environment is so great and the teachers so much better than even the city middle school I’ve been attending. I’m learning how to do graphic design, something I really aim to develop in high school. For the first time, I feel like I’m good at something and I don’t want to give it up.

Remember when you once told me that “there’s nothing for me in Binzhou except the dumplings.” (I do wish you and grandpa would come live with us in Beijing someday, maybe when I get a job…) That’s why I know you would understand because you have encouraged me to remain in Beijing.

If mom and dad truly know what’s good for me, then sending me back isn’t the answer. I was raised in this city, my entire life has been a Beijinger—I know no other home.

Reason One

Let me tell you all the reasons why I don’t want to return to laojia. Perhaps you can also use them to help persuade mom and dad to let me stay?

I’ve been with mom and dad in Beijing since three. As far as I know, for the last ten years, my home has been the apartment at the edge of Chaoyang District, not too far from Tongzhou, where I hear many migrants live.

But our neighborhood isn’t all migrants, there are quite a few local Beijingers scattered among us. And to be honest, I’ve never felt like a migrant—everyone here is nice to us and I have a couple close friends in the neighborhood too. Perhaps this is because my parents have done well for themselves. Not that we’re rich, but I think we are doing better than many others. They are the very few migrants who have bought their apartment here.

Neither of them went to college but they seem good at doing business. My dad runs his hardware store and fixes appliances all over Beijing—he even has good ratings from his clients on Dazhong Dianping! My mom has her own imported luggage store nearby and sells many of them on T-Mall. Though they work close, they hardly ever see each other during the day because they are so busy. It’s rare that they take a day off all week, especially now that dad has decided to make food deliveries on his moped to make some extra money on the weekend. Still, they always make an effort to be home with me for dinner and talk about school and discuss that day’s news.

I know they’re working so hard for my future and for their retirement, but I fear that they will work themselves to total exhaustion. They’re not that young anymore, and my dad already had a health episode a while ago, I think it was an ulcer. Thankfully he recovered after several weeks of rest and treatment with Chinese medicine. Neither of them has urban health insurance or pensions, only rural pension coverage that’s barely enough for the both of them. How can they enjoy their retirement if they can’t take care of their health? And how can I leave them when they need my help?

Reason Two

I truly feel like I’m getting a great education in Beijing. My daily commute is long, about an hour and a half, as I take the subway on my own into the city. But it’s worth it, because my teachers and my classmates make me feel like I belong. You might not believe me, I haven’t felt like they look down on me as a migrant, and my teachers like me because I’m one of the top students. I love algebra and drawing, especially Japanese comics.

My dad says I shouldn’t like Japanese culture so much because they invaded China. But I can’t help it, my friends and I are obsessed with Japanese manga and frequently visit shops after school to find the latest comics. There is just so much to do after school in Beijing. Even though I can’t afford it all the time, my parents give me enough allowance so that I can occasionally get bubble tea and McDonald’s with my friends. We have so much fun together, even when we’re helping each other on our homework. And I have to tell you this (but don’t tell mom and dad), there’s a girl in our group that I like…she likes bubble tea as much as I do!

On most weekends, I’m either finishing up my homework or watching anime with friends from the neighborhood. There’s one guy, a couple years older than me, he’s so cool that he’s taken me to see some Western movies and even taught me a few phrases in German. I really enjoyed Star Wars—the special effects were so dazzling. But I also miss seeing my parents on the weekend like I used to. In elementary school, they would take me to parks and temples all around Beijing, constantly explaining some aspect of Chinese history that I didn’t really understand. I didn’t mind though, I just enjoyed being with them. It has been years since we’ve done that.

Then again, lately I haven’t had much time for comics or bubble tea or parks, because I’m doing something even better. I don’t even know how dad found out about it—he said it was advertised in his WeChat group—but he got me into this new education center in Beijing that was created to support and educate young people like me.

Let me tell you grandma, I’ve never been to any place like this—the things they teach you aren’t like what I learn at school. There are hardly any textbooks in the classrooms, just computers, tablets, board games, and puzzles. On the first day, the founder of the center came to talk to us. She looked so young and yet so polished and successful. She told us that she was once a migrant Dreamer like all of us, having experienced the pressure and hardship of not knowing if you were going to make it or go back to laojia. She wants her business to help our generation of Dreamers so that we start off on an equal footing.

I couldn’t help but be inspired. I had thought our family’s life was good for our social station, didn’t realize anything else was remotely possible. So for the past six months, I’ve spent many evenings and weekends at the center, absorbing knowledge and making new friends. My teachers, who are all young, hip, and very encouraging, directed me toward graphic design and animation because they saw I had a knack for drawing and comics.

This may sound silly, but I think I found my passion. These computer programs were completely foreign to me, but I’m improving every day. I find it difficult to even leave the classroom and would rather keep on working on my graphics and 3D characters. Even the teachers have noticed my progress and have moved me up to an intermediate class.

Reason Three

I would be abandoning my future. I know what mom and dad want is the normal way—you return home before high school to take the exams. And if you’re lucky and do well, you go to a nice high school and prepare to take the gao kao. Maybe, just maybe, I will get a good enough score to come back to Beijing for college. But we have to score so much higher than the urban students to have a shot, it’s just not fair!

That’s how it goes, and several of my migrant friends have been forced into that “choice.” A couple of them call me every other day to complain, some even cry because they cannot bear being stuck in laojia. They just cannot get used to it—their boarding schools are stifling places, the curriculum is so boring because it’s all about taking that stupid gao kao. They have no friends, no family to lean on, and they beg to return to Beijing. They sound so distraught when I talk to them yet I can’t do anything. This is so common among us young people that they even have a term for it hou niao (候鸟), or “migratory birds.”

Dream Not Deferred

Why should I give up the best thing that’s happened to me for misery? I haven’t dared to tell anyone yet, because I’m afraid of the total disappointment from mom and dad. But here goes: I’m no longer sure I want to go to college—I think I’d rather go to technical school, or maybe even the Beijing Film Academy, to get more training on graphics and animation. I still can’t get that Star Wars movie out of my head…I want to make animation like that.

If they could see these thoughts, they would immediately yank me out of the education center. They would think that it’s all those young teachers’ bad influence that has placed these ridiculous thoughts in my head. They would scold me for not respecting their wishes and for wasting their hard-earned money on useless skills and idealism.

But they would be wrong. Those teachers didn’t pollute my mind; instead, they’ve made me feel confident, like I can achieve something in my life. And that young founder, she showed me that the conventional path isn’t necessarily the right one and that migrant or not, our generation is entitled to opportunity and choice, just as everyone else.

Ah, but I don’t know what to do or what I can do, as I’m completely dependent on mom and dad. They have sacrificed so much, how can I disobey? But they must know that I can’t be “deported” back to laojia just like that, it would be the end of everything good in my life.

I don’t want to be a hou niao…I don’t want my dream deferred.

In Their Own Words

We interviewed real migrants in similar cohorts to magnify their lives. Listen to each about their experiences, worries, and hopes.

To listen to other migrants’ stories visit the profiles of Zhou Xiaofeng, a blue-collar migrant, and Yan Zi, a white-collar migrant.

Other migrant stories

Hukou Difficulty Index