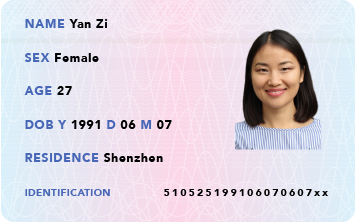

This white-collar migrant pens an open letter on her blog. The daughter of Zhou Xiaofeng, Yan Zi (her nickname) is a millennial migrant who has had improbable success in Shenzhen as the founder of an education startup.

I’ll just come out with it: I’m beyond elated to announce that I just closed Series C funding! We now have $30 million to scale up and ensure that we can bring the same standard of services and operations across all our existing and future centers.

This is also a testament to the success of our Beijing flagship center, where we’ve demonstrated that a scrappy startup like ours can do well by doing good—giving young migrants, these Dreamers, a better shot at their future through accessible private education and tutoring.

To my investors, I know all of you, especially after having personally met some of the students enrolled in our centers, are also aligned with the larger mission of turning these kids into full-fledged and valuable participants in the future of our country. It’s this mission-driven zeal that has kept our momentum for the last five years. Perhaps you, too, could see my unrelenting belief that these Dreamers need to realize their potential rather than being consigned to the margins of urban society or pegged as just another “returnee” to their rural hometowns.

The last few years have been frenetic. Plenty of mistakes were made and yet still, we have reached that inflection point for which we’ve always strived.

And that’s why I’m taking the opportunity to write this open letter on my blog. It is important that you, our supporters and customers, understand why I’m doing this. This is not just a startup business—it is the embodiment of what my life has been. This is personal.

The Need to Escape

Some people tell me that I am an unconventional founder and that my success is improbable, mostly because of who I am: a female Millennial migrant. True, handicapped by my gender and my pedigree at the get-go, the likelihood of success in the tech world falls pretty close to zero—especially in China, where migrant women in tech are almost always on the assembly line. On top of it, I don’t have fancy graduate degrees from top universities and never had a large network of people to lean on.

But I didn’t pick up my life and leave EVERYTHING behind just to become another dispensable pair of hands welding widgets. I wasn’t interested in being another statistic, to have the term “migrant” be synonymous with “street peddler” or “delivery girl” or “construction worker” or “factory cog” or worse yet, “social detritus.” Most of all, I couldn’t bear to imagine that another generation of migrant teens would have to accept that their fates are tied to their birthplace, from which they could never escape.

I escaped. First from my village in Huidong County in Sichuan, then from Chengdu to this shiny new Silicon Delta. To say that this required sacrifice would be a gross understatement. Some people are born with a winning lottery ticket in their mouths, I was born with a rural hukou. If it weren’t for my mother’s insistence and determination to make it out of that dead end of a village, I wouldn’t be writing this today.

She was a tenacious woman, the leader of the family, unlike my absentee father. He always talked big and thought he would show us the way by abandoning us for Shanghai—in pursuit of becoming a restaurant proprietor with nary a plan or capital. I hardly saw him for five years, and by the time he returned even more broke than when he left, my mother had already moved us to Chengdu. It nearly ruined my family—and I grew distant from him.

My mother didn’t know how to rest. As long as I’ve known her, she has held at least three jobs at the same time. I never knew how she found time to review my homework. But she would, until the wee hours of the night. I would wake up the next morning to find my homework stacked next to the bed, with notes written on it that said “satisfactory” or “you can do better.” For a woman who only graduated high school, she had incisive comments on my essays. It was the first inkling I had that credentials did not equal intelligence.

She died suddenly when I was 16. Overworked and hiding illnesses that were not diagnosed, she collapsed suddenly one night just like that. Perhaps seeing a doctor would’ve helped, but she refused to spend savings on healthcare because they were all meant for me and my education. She and dad had hidden their savings for years.

I went numb after that and turned inward. My father took it even harder, he looked broken for years. It was during those dark years that I realized my resentment toward him was unfair. He left us not because he wanted to but because he felt that he had an obligation to at least try to build a better life for our family. He loved us, and his way of showing it was to bear the risk himself and give it a shot, even if it meant returning to an estranged daughter who, at the time, neither understood nor appreciated his sacrifice. After that, I had to mature into an adult in a hurry, which actually somewhat repaired my relationship with him—we had no one but each other to lean on.

Through it all, I never lost my fierce independence and ambition to escape. Like my mother, I was always restless, especially as my head swirled with her mantra: “If you don’t make a better life for yourself and succeed, I will come back and haunt you.” Success, at least how I imagined it, was never going to be found in Chengdu.

I harnessed all my energy and focus on finishing school and taking the college entrance exam. The bar is higher for us migrants, and I had aimed for a prestigious provincial university to study economics. The first taste of success came when I was accepted to the Southwestern University of Finance and Economics.

I hardly socialized in college, as I constantly felt like a square peg in a round hole among my urban classmates who were mostly local residents. It was subtle, but I could always sense that they questioned my intelligence because I didn’t know the latest foodie or fashion trends. They weren’t mean people, it was just a habitual, casual bias that people like me are supposed to grow accustomed to. So I had extra time and took up learning how to code and develop software, and I became pretty capable after a couple years.

A year before graduation, I had already decided that I had to go seek the future, and that meant the coastal metropolises. It had crossed my mind that I could fail just like my father. But I made a promise to myself, no matter the challenges and defeats, I was going to always move forward. Once I left, I would never look back.

I never told my father this. But I think he sensed it that day on the train platform—it was the first time I saw tears well up in his eyes. Intense remorse and shame swept over me—after resenting him for abandoning us all these years, I’m now doing the exact same and justifying it in my own terms.

My mind was on fire. Fighting back tears, I simply muttered “take care of yourself” and disappeared into the train. I didn’t know when I would see him next.

Not Looking Back

I didn’t recount my story to elicit sympathy. Rather, it is an all too common tale of broken homes, higher barrier for receiving quality education, subtle and overt discrimination—all factors that create chasms between people like me and the true urbanites.

Indeed, when I first arrived in Shenzhen five years ago from Chengdu, I had deluded myself into thinking that fitting in would be easy, that these barriers would dissipate. After all, Shenzhen is a young and techie town where most everyone is from somewhere else, nearly two-thirds are migrants in fact. It is a city erected from the swamps by migrants.

But it quickly became obvious to me that I stood out, not specifically because of my identity as a migrant or woman. In fact, like most Millennial migrants in my cohort, there is a high level of acceptance from locals, and social barriers are not immediately obvious on the surface.

Rather, I was the odd duck who didn’t accept my place in the pecking order. Migrants are supposed to be the labor supply, not the CEO.

I knew my training would be useful in Shenzhen. But amid a sea of college graduates and coders, I was hardly distinguishable. In fact, my training and education might prove a disadvantage, as I’m competing directly with locals for limited professional jobs. None of this was overt, but I felt it viscerally. The most pernicious form of discrimination, I discovered, is the one that is unspoken and therefore makes you feel helpless.

So I just had to keep on moving forward. Fortunately, my coding skills caught the eye of a small, guerilla software company that was a contractor for developing apps, everything from pet services to e-healthcare. They paid well, at least by my standards—at 12,000 yuan/month with an occasional bonus if business was good. At the time, I thought that was the most money I could possibly make on my own.

It was there that I met who would become the first few members of my startup team—all of them migrants that hailed from places like Hunan, Shandong, and other parts of Guangdong. In between long and intense coding sessions, we bonded over beers and Sichuan hotpot. Not everyone could tolerate the spice, especially the northerners among us, but we all quickly found a common thread: the inability to reconcile how we made it out with the nagging sense that few understand what it took out of us and how many of us remain stuck.

Conversations often veered toward debates on social stratification—not just between urbanites and rural migrants, but particularly among migrants themselves. Relative to the 280 million or so migrants in China, we are probably the one-percenters.

We are under no illusion that we are the lucky few, the flat part of the bell curve. Look at our lives now. All of us rent apartments in high rises near work, and the luxury of being single is that each of us has plenty leftover to pursue our own interests. Disposable income was largely a foreign concept to our parents, but we hardly hesitate to spend on restaurants, vacations, and even self-improvement like gym memberships.

Yet what I describe here is barely recognizable to the daily lives of the vast majority of migrants here in Shenzhen, young like us but a whole world apart. Even before I had my company, my salary at the time was already more than double or even triple theirs, and they could hardly think about spending beyond general necessities. The urban, cushy lifestyle to which they aspire is not within grasp.

There are many more of them than us here in Shenzhen and across the country. Yet the vast majority of them insist on staying, to try their luck in the hopes of climbing the social totem pole. Many of them even intend on owning a home, putting down roots with their families. They have absorbed the aspirations around them and like me, they aren’t willing to look back.

We Were Once Dreamers

It has dawned on us, more than once, the irony, or really the hypocrisy, of our lives. Yes, we all have some kind of college or technical degree and equipped with 21st century skills, yet we are now making apps that will likely require the labor of that other 99%, many of them migrants in my generation who never got a fair shot. How is this a worthwhile use of our time and our talents?

The answer to that question led to the genesis of our social impact venture “Future Capital.” I never thought I was founder material, but it turned out I had a knack for being annoyingly persistent in pursuit of funding. I cold-called and networked incessantly, in the hopes that I’d inspire likeminded investors.

While the education market is booming in China, migrant children have been neglected for the obvious reason that migrants can’t afford expensive fees. Nobody could see a business case for offering better quality private education to migrant children who, in most cases, have to return to their hometowns starting in high school. Once they return, their chances of success diverge significantly from their peers in urban areas—many fall through the cracks or in some cases, join the military, hoping against hope of returning to the city someday.

But our venture is not merely about an immediate return on capital or short-term profits, but about investing in a long-term return on human capital. Rather than waiting for this embedded and distorted system to become fairer, we want to play a small part in shaping future generations’ outcomes, so that they do not largely rest on luck.

In the eyes of many, I now may be viewed as a wealthy founder. But I was extraordinarily lucky, and my odds would’ve been even more precarious if I didn’t push beyond my limits. It shouldn’t have to be this way. We owe it to ourselves to address these inequities because we, too, were once these Dreamers.

In Their Own Words

We interviewed real migrants in similar cohorts to magnify their lives. Listen to each about their experiences, worries, and hopes.

To listen to other migrants’ stories visit the profiles of Zhou Xiaofeng, a blue-collar migrant, and Luo Xinnan, a teenage Dreamer.

Other migrant stories

Hukou Difficulty Index