- September 25, 2024 Energy

Will China Really Achieve Peak Carbon Next Year?

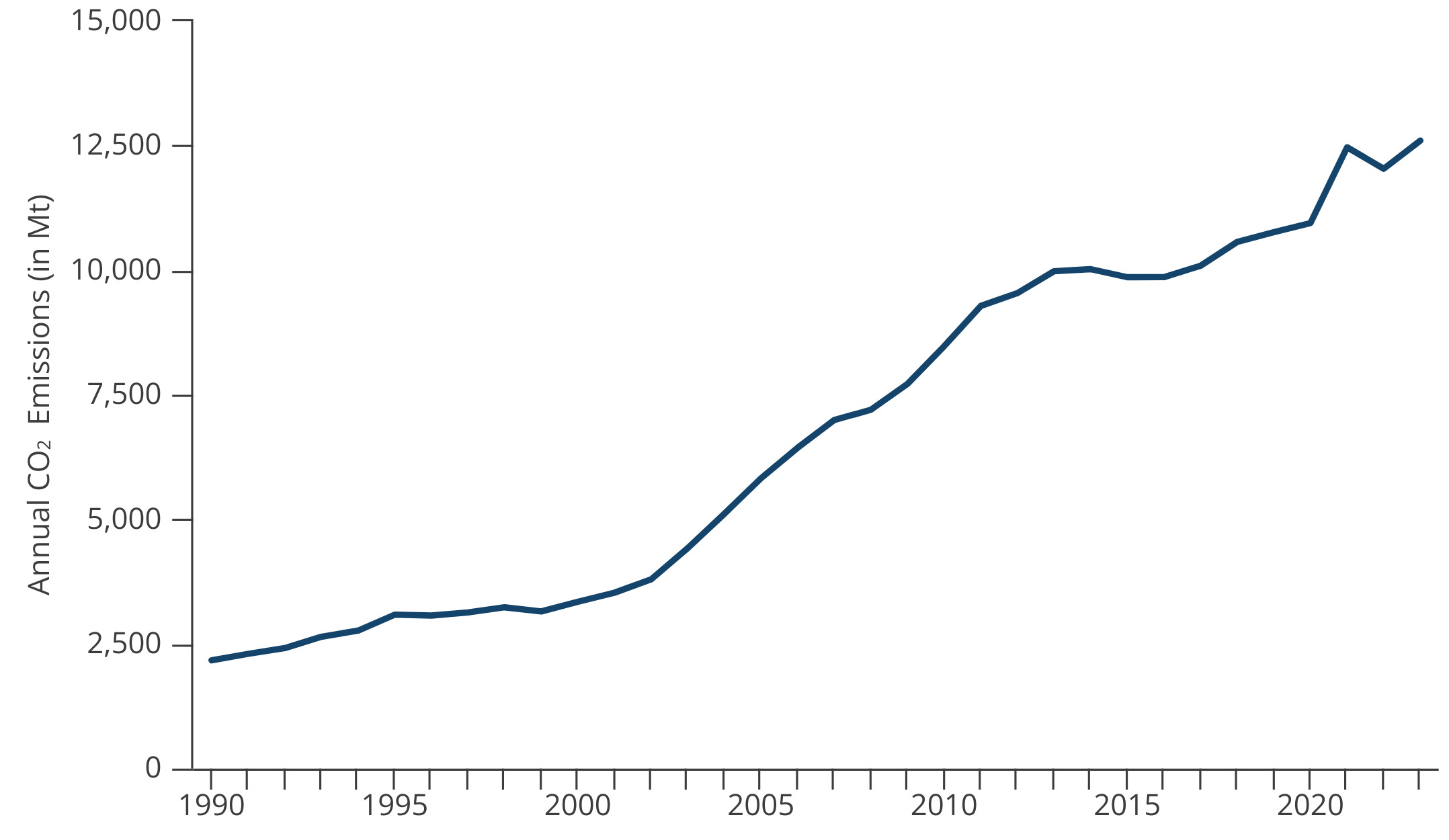

To date, China’s biggest move on climate has been its “30/60” commitment—the twin goals of peaking carbon emissions by 2030 and achieving carbon neutrality by 2060. Now that the first goal is just five years away, there’s a lively and ongoing debate over whether Beijing will shatter all expectations and deliver peak emissions as early as 2025 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. China’s CO₂ Emissions Increased More Than Sixfold Over Three Decades

Source: World Bank; International Energy Agency.

That debate has pitted the “believers” against the “skeptics” in assessing what is realistically achievable for China. While some recent trends may augur well for the “believers,” we think some healthy skepticism on early peak is warranted.

2023 a Turning Point?

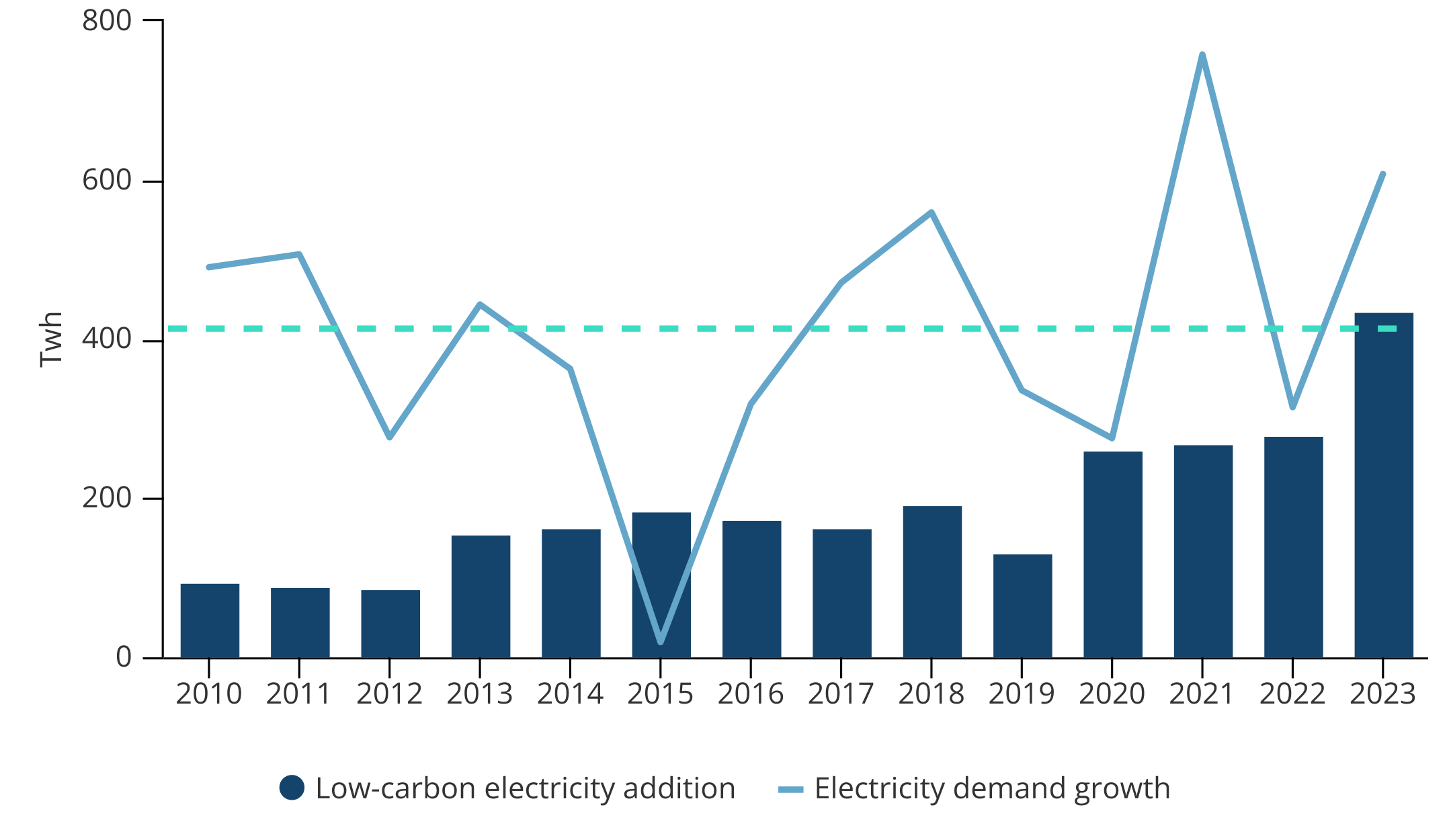

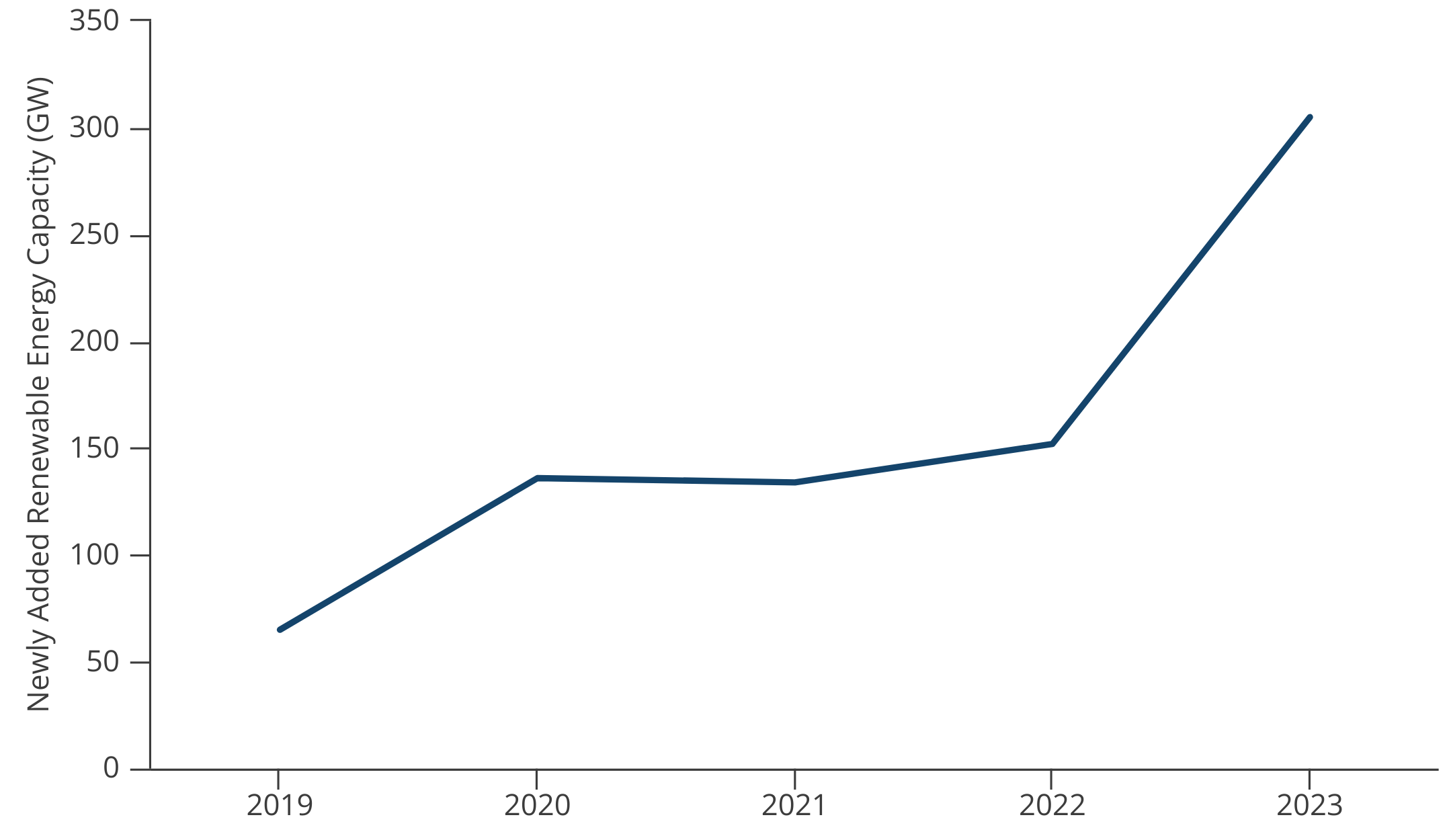

Much of the euphoria over peaking early seems to be fixated on 2023 being a banner year for renewable energy expansion in China. For instance, last year marked the first time China’s low-carbon electricity production topped the country’s average annual increase in power demand since 2010. Moreover, China’s installed renewable energy capacity hit 1,653 GW in mid-2023, already 400 GW more than the goal it originally set for 2030 (see Figures 2 & 3).

Figure 2. Low-Carbon Electricity Growth Outpaced Electricity Demand Increase

Source: Ember Climate; Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air; China Electricity Council.

Figure 3. 2023 Was a Monstrous Year for Renewable Energy Installations

Source: National Energy Administration (NEA); State Council Information Office.

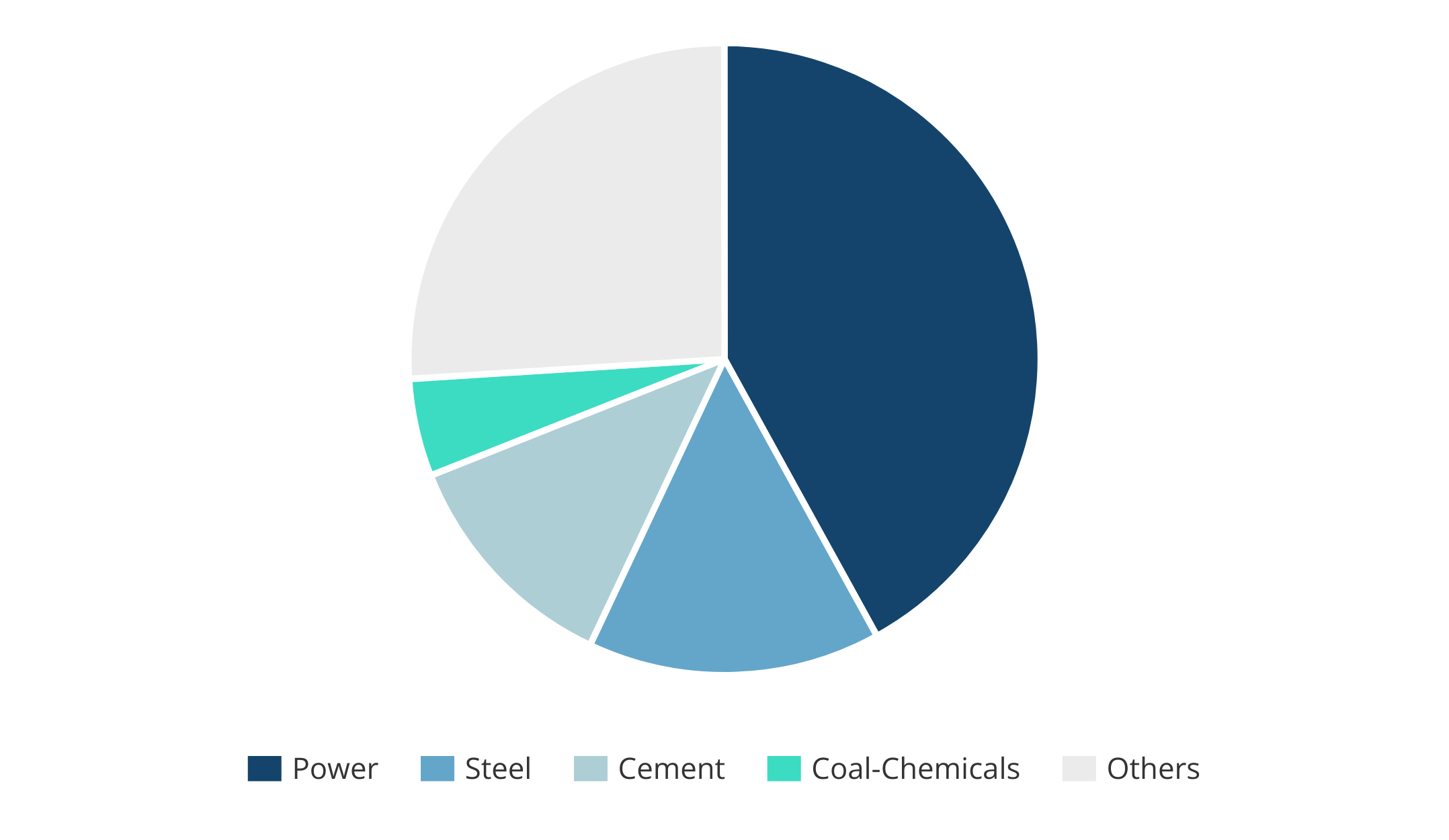

Meanwhile, China’s secular economic slowdown, centered on the massive correction in the property sector, also contributes to lowering emissions even if it’s difficult to determine precisely the scope of contribution. That’s because the property market collapse curtails demand for steel and cement, the types of heavy industries that rank as the second- and third-largest contributors to carbon emissions (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Four Industries Account for 75% of China’s Total Carbon Emissions

Source: Natural Resources Defense Council.

Let’s Not Get Too Carried Away

So was last year the beginning of the end of fossil fuel’s dominance in China’s energy mix, meaning the imminent arrival of “peak emissions”? We think that’s a premature call.

The surge in China’s renewables capacity has indeed been impressive and will likely continue as the country added another 134 GW of renewables in 1H2024 alone. That is only part of the story, however.

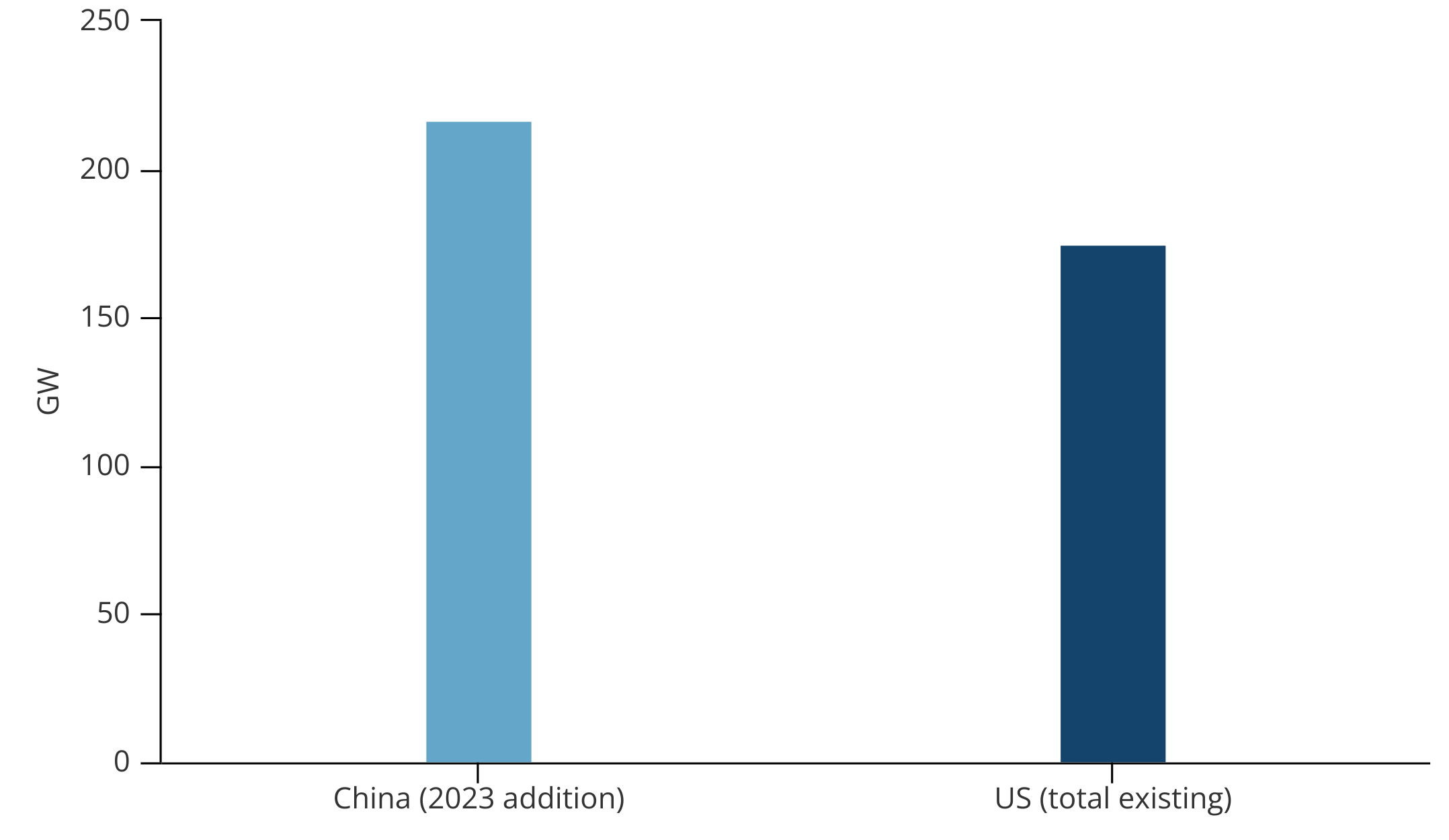

It would appear that much of the additional renewables capacity was a way to digest significant overcapacity in China’s solar industry. For instance, China’s solar production capacity of 861 GW in 2023 could have satiated existing global solar demand twice over and still have had additional capacity to install at home. In fact, about a quarter of that capacity, or 217 GW, was installed in the home market—that was more solar installed in a single year in China than the entire existing fleet in the United States (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. China Installed More Solar in 2023 Alone Than All US Capacity…

Source: NEA; Bloomberg.

Moreover, simply installing solar panels doesn’t do much to curb emissions—it matters how much of that capacity is actually being used. On this front, China still faces the perennial problem of underutilization—in regions like Shandong, for example, 50-70% of distributed solar generation is curtailed to balance with demand. This is the result of longstanding issues of an inflexible grid system and regional imbalances in transmission and distribution that won’t be resolved anytime soon.

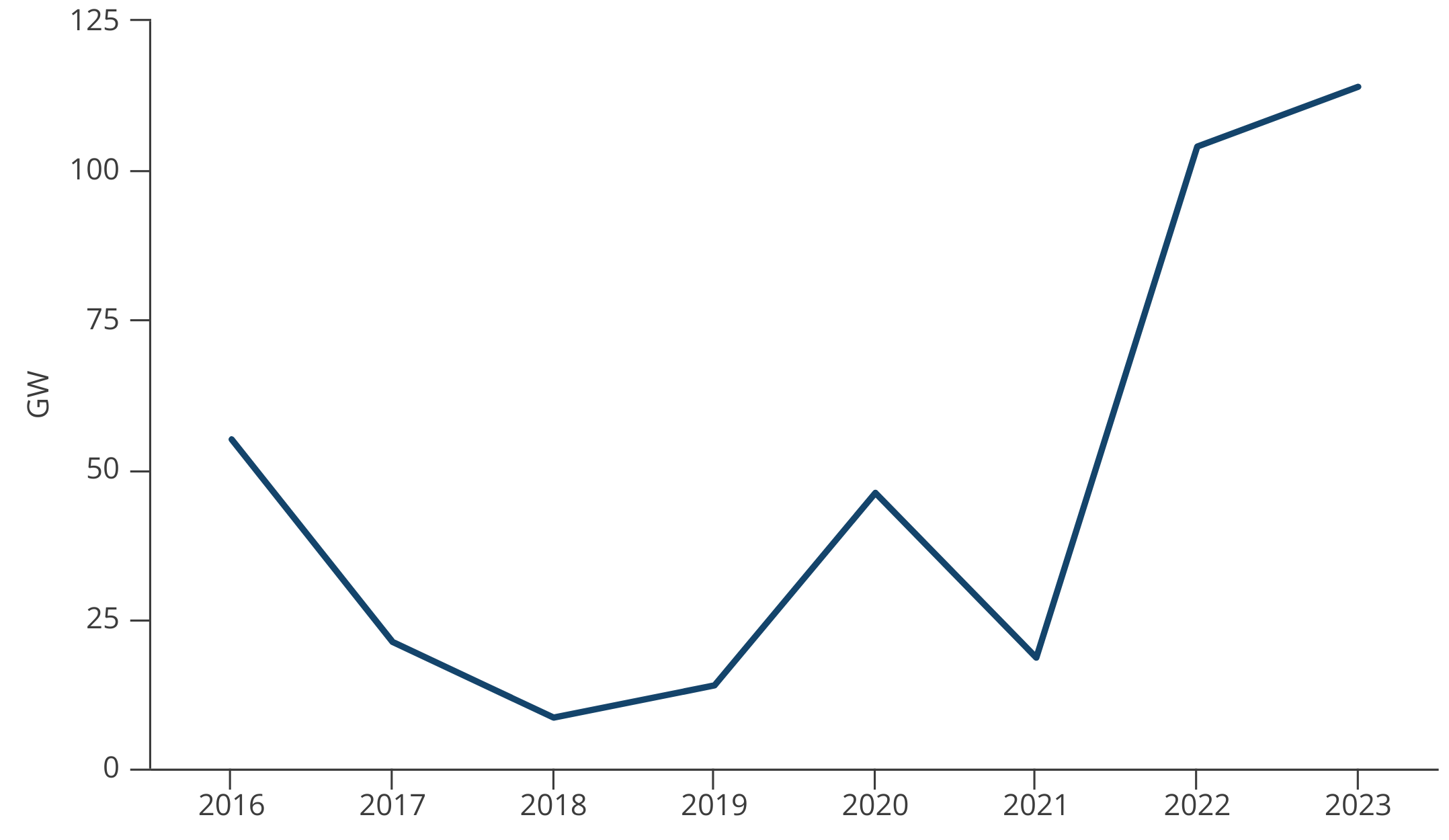

Figure 6. …Yet Also Approved More Than 200 GW of Coal Plants in Two Years

Note: China approved over 100 GW of coal power in both 2022 and 2023, which translates to more than 100 coal plants per year.

Source: Greenpeace; Global Energy Monitor.

The focus on the extraordinary additions of renewables 2023 has obscured what a banner year 2022 was for coal (see Figure 6). While most of these projects haven’t yet broken ground, the approval pipeline implies they will be coming online over the next few years, which would offset some of the renewables capacity.

Finally, Beijing officialdom so far doesn’t seem to share in the enthusiasm of early peaking, or they’re certainly not showing it. In August, the National Energy Administration (NEA), the closest thing China has to an energy regulator, released a white paper that offered little clarity on the road ahead for China’s energy transition. When asked about an early emissions peak, an NEA official made it clear that China is holding to the 2030 peaking target.

While China will certainly earn plaudits for achieving peak carbon ahead of schedule, what matters much more is how fast emissions fall after the peak. If the country’s emissions level stagnates after the peak, then hitting that point will quickly lose its punch. And what comes after the peak ultimately hinges on Beijing’s priorities, which will be on display in the upcoming 15th Five-Year Plan.

Amy Ouyang is a research associate at MacroPolo. You can find her work on the global energy transition and its intersection with the economy, technology and industrial policy here.

Stay Updated with MacroPolo

Get on our mailing list to keep up with our analysis and new products.

Subscribe